Among political scientists, it is a truism that many working-class white men left the Democratic Party in 1968, voted largely Republican in 1972, came back home for a moment in 1976, and switched to Ronald Reagan in 1980 (a detailed analysis here). Many pundits think that Bill Clinton "won many of them back to the Democratic Party in 1992," but data do not support this opinion. Exit polls actually show that in 1992 Bill Clinton won about the same share of white men as Michael Dukakis in 1988. It was Ross Perot who moved many of them away from the Republican candidate and undid George H.W. Bush.

Democrats have been the party of minorities since 1972, and they did not really compete for white men since the Ford-Carter race in 1976. But in 2008, whith the Republican Party and its standard bearer remarkably unpopular, a war led by Republicans that has lasted longer than Second World War, during a struggling economy, and at the 40-year mark of the Republican majority (no presidential coalition has ever lasted more than four decades: the New Deal one survived only 36), Democrats have their best opportunity in a generation. Yet the Democratic ambition will only be realized by winning more white men, as many scholars realized a few years ago (see, for example, Ruy Teixeira).

It’s not only a southern problem: the bulk of the white men voting in Democratic primaries are not the same white men who migrated from the Democratic Party in the last half century, as David Kuhn has demostrated in his book, The Neglected Voter: White Men and the Democratic Dilemma. Contrary to New York Times’s Paul Krugman opinion, it was not only Southern white men nostalgic of George Wallace who left the Democratic Party. Krugman quoted Princeton's Larry Bartels as saying that outside the territory of the 11 Confederate States, “[in] the rest of the country the Democratic share of the two-party presidential vote among white men was 40% in 1952 and 39% in 2004."

Bartels uses 1952 as a starting point but that year both parties attempted to convince Dwight Eisenhower, a centrist who was the hero of the Second World War, to be their nominee. When Ike chose the Republicans, many white men followed him, giving to the Democrats an unusually low share of the vote. Therefore, the 1960 race is a more accurate starting point: It was a narrow contest and prior to the shift of 1968 that defines presidential politics to this day.

Looking at 1960, one discovers that between that year and 2004, Democrats lost 12 percent of the non-Southern white men and 17 percent of white men in the South: simply too much to win the elections. Conventional wisdom dies hard in presidential politics but clinging to it will damage the Democratic party for many years more.

This year, white men initially backed Clinton: their first instinct was to be with the frontrunner. But unlike white women, as Obama became more widely known, white men had no stake in the symbolism of her candidacy. Therefore, they were more willing to swing to the senator of Illinois.

Many of these men casting Democratic ballots today are of the 37 percent of white males who voted for John Kerry in 2004, a share of the vote that left the Democratic candidate 3 million votes behind George Bush. Yet, so far neither Clinton nor Obama understand exactly how to reach out to them, a problem critical to a victory in November, when John McCain will flaunt his military record in order to appeal to this key constituency. In John McCain, any Democrat will find a daunting opponent with white men. He is the embodiment of much they admire.

A simple look at the 2004 exit polls provides a telling lesson for Clinton and Obama. Those white men who voted for George W. Bush in 2004 said the "issue that mattered most in deciding their vote" was terrorism (35 percent) or moral values (31 percent). Yet among the minority of white men who voted Democratic, only five percent said terrorism and 10 percent said moral values. In other words, Clinton's muddled stance on Iraq and hawkish stance on Iran was wrong for most Democratic white men.

For those Democratic white men, the foremost issue in 2004 was Iraq (26 percent) and economy/jobs (35 percent). Clinton's recent effort to mount a broad economic appeal may prove too late in a year when economic catastrophe for millions of American families is already there.

Clinton failed to consider white men in her strategy. Obama's campaign was more successful (particularly after Edwards drop off) because his broad appeal, less obsessed with individual subgroups. He reflected the framework of the Democratic mind in 2008 and therefore attracted white men sympathetic to that mind.

Consider when 2004 voters were asked what issue mattered most in deciding whom to support. White men who voted Republican said they supported the candidate who "has clear stands on the issues" (30 percent), is a "strong leader" (31 percent), or is "honest and trustworthy" (18 percent).

Meanwhile, of those white men who voted for John Kerry: five percent valued that their candidate was a "strong leader," 10 percent valued most that he had "clear stands on the issues," and nine percent said is "honest and trustworthy." White men, like white women, are not one monolith. Yet in the general election, the patterns shared by all those white men who left Democrats will have to be considered by the political left.

Those white males who supported Kerry most valued the personal qualities of a candidate who "will bring about needed change" (47 percent), is intelligent (17 percent), and "cares about people like me" (13 percent). That "change" ranked so high on the list explains Obama's appeal, at least in part.

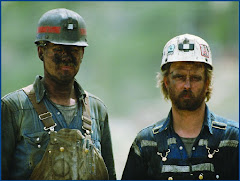

Using education level as an indicator of social class, you find that white male Democrats without college educations are roughly three times more likely than those who graduated college to value that the candidate who "cares about people like me." In comparison, those who graduated college are roughly three times more likely than those who did not value that the candidate "is intelligent." White male Democrats who graduated college were also three times more likely to say the issue that mattered most was the war in Iraq, where Obama benefited from his early stance against the war. It is no surprise that they would be more sympathetic to Obama today.

Equally, that working class white male Democrats want to believe that the candidate "cares about people like me" certainly explains in part why Clinton has generally held on to their support. Obama's strategy to leave behind the cultural politics of the '60s and run a post-racial campaign appeals to some independent white men: will that be enough? In the 2006-midterm elections many white men were open to supporting Democrats, particularly moderates, even in states like Virginia and Montana, where George W. Bush got 60 percent in 2004.

It will be this presidential election that tests whether Democrats can turn working class men’s frustration with Republicans into a new majority. This is why the contest for white men is larger than the Democratic primary and is a harbinger for who becomes America’s next president.