Washington DC - "It would have been difficult four years ago to schedule a meeting with the President to discuss with him the fact that there were too many people in this country getting houses," says Marc Summerlin in response to a question on the crash of the housing market at the book launch of What a President Should Know, which he co-wrote with Lawrence B. Lindsey. "In retrospect this would have made perfect sense."

Marc Summerlin served as Deputy Director of the National Economic Council for President George W. Bush, while Lindsey was Director of the NEC. They both now work for the Lindsey Group, the economic advisory firm based in Washington DC that they co-founded.

Their book, presented at the Council on Foreign Relations on Monday, offers an insider's look at the Oval Office: Through a review of the history of the office of the Presidency, the authors portray the constraints under which the Executive makes decisions. Summerlin and Lindsey also highlight the difficulties, even for the closest advisers, to have regular visitations with the President. With many competing issues that at all times require urgently the attention of the President, some necessarily end up to the sideline, often those that have longer-term effects.

The history of the architecture of the Oval Office itself stands as a symbol of how access to the President has been restricted through the decades.

The idea of the Oval Office was first conceived under Teddy Roosevelt and was finally built at the beginning of the Presidency of William Taft in 1909, in the shape of an oval precisely because it was the one that allowed for the largest number of doors to be added. Teddy Roosevelt wanted as many people as possible to enjoy direct, walk-in access to him.

Under the first "Imperial Presidency," as Summerlin described Franklin Roosevelt's three-term government of the United States, the West Wing - where the Executive meets - was moved and expanded, and the Oval Office was relocated to a side of the building with only one door opening onto it. "Such change was followed by the creation of the role of the Chief of Staff", said Summerlin at the Council on Foreign Relations, "that from then on strictly regulated access to the President," and with that the flow of information that made its way all the way up to the top.

Today, White House advisers have to fight among themselves to be able to see the President and documents containing important information must be signed by tens of people in order to make it to the desk of the Commander-in-Chief.

The most important advice that Summerlin, and Lindsey, would give the future President is to "truly reinforce those people that are advising him/her honestly, because it is hard to find such people."

MORE MONEY THAN DURING WORLD WAR II...

SATURDAY NIGHT LIVE

- "It was so cold today, I was shaking like Sarah Palin taking a geography test" (David Letterman).

THE GREATEST POLITICAL ADS OF ALL TIMES

SOURCES

WHAT BARACK IS READING ON THE PLANE

WHAT BARACK IS READING WHEN FORMING HIS CABINET

READING OPPORTUNITIES... MAYBE

STILL IN PRINT?

"Despite the Bush Administration's current unpopularity, the Republican domination of American politics is unlikely to end anytime soon." (2007)

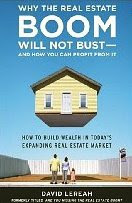

STILL IN PRINT?

"Continued low interest rates, a healthy boomer population, should keep the market healthy for at least the next 10 years." (2006)

STILL IN PRINT?

"The Democratic Party can no longer field a serious presidential challenge." (2003)

ARCHIVE

-

▼

2008

(152)

-

▼

April

(19)

- Harvard: Millions of Americans "Without any visibl...

- Populist Commercials and Oil Money

- The Day After

- The DUEL Will Go On And On...

- Zero Tolerance Comes To Italy

- How ABC Set A Trap To Question Obama's Patriotism

- Hillary Clinton, Religion and The White Working Class

- Benedetto XVI, George W. Bush and How To Get Throu...

- Sins, Bad Memory and The Future of The Country

- Is John McCain A Strong Candidate?

- Even The New York Times Realized That...

- When Life Imitates Art... It's Not Pretty

- Are intra-party feuds fatal in November?

- Clinton goes to Jay Leno's show to defuse issue of...

- For those who thought the crisis was over...

- Indianapolis, April 4, 1968

- A VIDEO THAT WILL HAUNT HILLARY FOR A LONG TIME

- There would be hell in the party for a long time/5

- WHAT A PRESIDENT SHOULD KNOW

-

▼

April

(19)

INDEX

- Alaska (4)

- Bank lobby (1)

- Breaking News (6)

- Crime and Politics (1)

- Cuba (1)

- Defense Policy (1)

- Democratic party (44)

- Economy (17)

- Electoral College (6)

- Financial Crisis (1)

- Florida (4)

- Foreign Policy (2)

- George W. Bush (3)

- Historical Documents (1)

- House of Representatives (2)

- In the News (7)

- Judicial Elections (1)

- Late night shows (1)

- Long-term political trends (10)

- Media and Elections (4)

- New Books (2)

- Oil lobby (2)

- Political Communication (8)

- Political culture (2)

- Political structures (1)

- Politicians as performers (2)

- Poverty (1)

- Public and Private in American Politics (3)

- Racism in American society (4)

- Religion and Politics (3)

- Republican party (22)

- Robert Kennedy (1)

- Ronald Reagan (1)

- Satire (3)

- Technology (1)

- Turnout (8)

- Vice president (1)

- Vote Fraud (2)

- Welfare (1)

- White Working Class (10)